-

-

The Hikers

-

-

Tundra Swans

-

-

Flying Snow Geese

On March 12th the Duncannon Outdoor Club went to the Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area to witness the migrating Tundra Swans and Snow Geese. Middle Creek Is an important way station providing food and rest for waterfowl flying to northern breeding sites. The warmer weather triggered an earlier migration, so we were lucky to see thousands of Snow Geese. The Tundra Swans were visible only through binoculars, since they had settled down far across the lake.

-

-

Watching people watch the birds.

-

-

Lunch Break!

-

-

A Vernal Pool

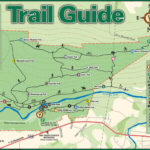

After taking pictures and observing the birds and the many people observing them, we headed to the Visitor’s Center to begin our hike along a series of trails. We started at the Conservation Trail to Spicebush Trail, up Valley View Trail, down Horseshoe Trail, to Middle Creek Trail, up Elders Run Trail, back to Conservation Trail to the Visitor’s Center for a total of six plus miles. The two climbs required some effort, but lunch after the first climb re-energized us for further challenges.

We could not believe that horses could traverse down the section of Horseshoe Trail which was nothing more than a narrow, steep, deep ditch down the mountain. Horseshoe tracks confirmed that it was possible. On the Conservation Trail we were lucky to see a vernal pool, a temporary pool of surface water, full of Wood Frog and Jefferson Salamander eggs, an early sign of spring.

![north-america-migration-flyways[1]](https://duncannonatc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/north-america-migration-flyways1-300x300.jpg)

As with every DOC event we had an outdoor educational theme. The theme for our event was Snow Geese and Tundra Swans so we had a brief presentation before starting our hike. First we reviewed the four major flyways in North America: the Atlantic Flyway (commonly known as the Kittatinny Ridge in the Harrisburg area), the Mississippi Flyway, the Central Flyway, and the Pacific Flyway.

(Please note that the Kittatinny Ridge is being threatened by development. Refer to Kittatinny Ridge for further information on this topic and to find what you can do to save the ridge.)

-

-

Tundra Swans mate for life.

-

-

The Tundra Swans use mostly the Pacific and Atlantic Flyways to reach Northern Canada and the Northern and Western edges of Alaska breeding areas. They leave their wintering areas at their lowest weight relying heavily on way stations like Middle Creek and the lower Susquehanna. When winter approaches, the Tundra Swans east of Point Hope Alaska winter on the Atlantic Coast flying 4,000 miles. Swans south of Point Hope follow the Pacific flyway to their wintering areas along the Pacific Coast.

Tundra Swans have black beaks, faces, and legs. There are small yellow spots in front of their eyes. Holding their necks in a straight position differentiates them from the Mute Swans, a feral or domestic non-native species, which hold their necks in an “S” position.

The Mute Swans are easy to tell apart from Tundra Swans, because they have an orange bill with a black knob at the base. This non-native species is very aggressive, taking and defending a half square mile as its territory. It is a very aggressive bird and will hiss, stare, hit with the wrists of its wings and attack humans. This behavior and a voracious appetite disturbs local ecosystems displacing native species like the Tundra Swan.

Tundra Swans are dabblers used to eating animal matter and nipping off submerged aquatic plants as deep as three feet below the surface. However, due to vanishing wetlands they have begun to feed on agricultural fields. Nipping off the tops of plants and eating seeds left behind after the harvest.

-

-

Nests are built high for better visibility.

-

-

Female Tundra Swans have 3 to 5 cygnets.

Tundra Swans build their nests out of grasses, sedge, mosses, and lichens on the ground in a place providing good visibility. Their territory covers a half square mile, but does not seem to impact the local ecosystem as negatively as the Mute Swans. Tundra Swan babies, called cygnets, are born with their eyes open and are in the water 12 hours after they pip the shell. They are light gray in color, are brooded by the parents for about a week, and are ready to fly after two or three months.

Continue reading →

![north-america-migration-flyways[1]](https://duncannonatc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/north-america-migration-flyways1-300x300.jpg)